Ghosts, demons, and spirits are the most popular creatures often associated with Japanese mythology but are far from being the only beings present. A lesser known entity is the Japanese dragon, which usually lives in water and shapeshifts into a man, if not a beautiful woman.

Although dragons may be iconic mythical creatures, as well, not a lot of people are aware of their roles in Japan’s classical legends. A common misconception when it comes to dragons is that all of them are exactly the same throughout Asia. This statement may be true to some extent but, essentially, each country has its own kind of dragons.

An Overview of Japanese Mythology and Japanese Dragons

Japanese mythology makes use of Shinto, Buddhist, and folklore beliefs for its creation story and succeeding legends. Upon the creation of the universe, it is believed that several deities came into existence, as well, and were collectively referred to as kotoamatsukami.

After heaven and earth were formed, seven generations of gods (individually known as kami) emerged and were regarded as kamiyonanayo or the Age of the Gods’ Seven Generations. According to the Japanese creation myth, the kamiyonanayo consisted of twelve gods, of which two served as the initial, individual kamis known as hitorigami, while the other ten emerged as male-female pairs, either siblings or married couples.

From these deities, many other gods and goddesses came into being, along with various creatures that served as their guardians, messengers, warriors, and enemies. Japanese dragons were unique in the sense that they served as water gods that ruled the oceans, fought with other gods, shapeshifted into humans, or vice versa. They were also believed to signify wisdom, success, and strength.

Famous Japanese Dragons – Names, Meanings, and Stories

Some of the first appearances of dragons in Japanese mythology were in the Kojiki (680 AD) and Nihongi (720 AD).

The Kojiki, also known as the Records of Ancient Matters or Furukotofumi, is a collection of various myths related to Japan’s four home islands. The Nihongi, which is also referred to as Nihon Shoki or The Chronicles of Japan, serves as a more detailed and elaborate extant historical record than the Kojiki.

In both documents, water deities in the shape of serpents or dragons are repeatedly mentioned in numerous ways. These creatures are considered to be Japan’s indigenous dragons, the most popular ones being:

Yamata no Orochi (八岐大蛇) – The Eight-Branched Giant Snake

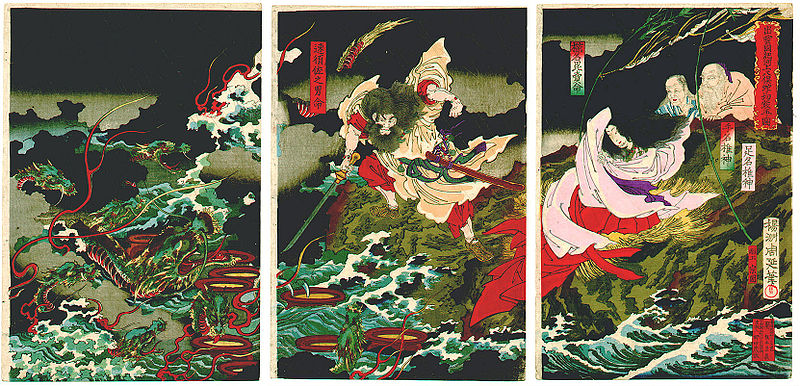

Yamata no Orochi, or simply Orochi, was an eight-tailed and eight-headed dragon who, every year, devoured one of the daughters of the kunitsukami, two earthly gods. The legend starts off by telling the story of how Susanoo, the Shinto god of sea and storms, was expelled from the heavens because of his trickeries towards Amaterasu, his sister and the goddess of the sun.

Near the Hi River (which is now referred to as Hii River) in the province of Izumo, Susanoo came across the kunitsukami, who were weeping about how they had to give up a daughter each year for seven years to please Orochi and would soon have to sacrifice their last daughter, Kushi-nada-hime.

Susanoo offered to help save Kushi-nada-hime in exchange for her hand in marriage. The kunitsukami agreed and Susanoo transformed their daughter into a comb right before their eyes. Then he tucked her into his hair and told the kunitsukami to prepare eight-fold sake and make eight cupboards, each having a tub filled with the alcohol.

When Orochi appeared, Susanoo saw that it had red eyes, an eight-forked tail, an eight-forked head, and growing cypresses and firs on its back. The dragon’s size spread over eight valleys and eight hills as it crawled towards the kunitsukami’s homeland.

Upon reaching the tubs, Orochi drank all the sake, became drunk, and eventually fell asleep. Susanoo took this opportunity to slay the dragon by using his ten-span sword to chop it into small pieces. As Susanoo split the dragon’s tail open, he found a sword inside, which would, later on, be called the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi – the same sword Susanoo would eventually give to Amaterasu as a form of reconciliation.

The sword, along with a mirror and jewel respectively called Yata no Kagami and Yasakani no Magatama, are considered to be the Imperial Regalia of Japan.

Watatsumi (海神) – The Sea God or King of the Sea

Watatsumi, or Ryujin, was a legendary water god and Japanese dragon in the world of Japanese mythology. Another name for the dragon is Owatatsumi no kami, which means “the great god of the sea” in English.

According to Japanese mythology, Watatsumi lived in a palace known as Ryugo-jo under the sea. It is believed that he served as a guardian for the Shinto religion and would welcome humans into his kingdom if they fell into the sea. He and his numerous daughters made frequent appearances in various legends.

One story in the Kojiki tells of how a man named Hoori lost his brother’s fish hook in the sea and, while searching for it, met Otohime, a daughter of Watatsumi. Hoori and the dragon goddess soon got married and lived in Ryugo-jo.

After three years, Hoori started feeling homesick and wanted to live on land, again, but was afraid of facing his brother without his fish hook. Watatsumi confronted Hoori about what was bothering him and upon hearing his concerns, the water god summoned all the fishes of the sea to ask if any of them had seen the fish hook.

Fortuitously, one of the fishes did come across the fish hook and had it stuck in its throat. It was obtained, washed, and given to Hoori.

Watatsumi then instructed Hoori to take Otohime back with him up to the lands using a wani, another mythical dragon best described to be a sea monster/creature.

In the Nihongi, Watatsumi also makes an appearance through the tales of Emperor Keiko and Emperor Jimmu. According to the texts, Emperor Keiko’s army came across harsh waters as they crossed the land between the province of Sagami and the province of Kazusa. This calamity was associated with Watatsumi, who had to be offered human sacrifices to be placated.

Watatsumi is cited in Emperor Jimmu’s story because of his claim to be a descendant of Toyotama-hime, the daughter of Otohime and Hoori.

Toyotama-hime (豊玉姫) – The Luminous Pearl Princess

Toyotama-hime, as previously mentioned, was a descendant of Watatsumi. She is also known as the Luxuriant Jewel Princess and appears in the legend known as Luck of the Sea and Luck of the Mountain. In this tale, Toyotama-hime is not introduced as the daughter of Otohime and Hoori but, instead, takes on the role of Otohime, herself.

Furthermore, Watatsumi recognizes Hoori to be a descendant of another god and quickly has a banquet arranged for him. The same events of the two getting married, living in Ryugo-jo for three years, and going back up to the lands remain true. Their life on land is then told in detail.

Upon the announcement of their pregnancy, Hoori built Toyotama-hime a hut where she could deliver their child. The goddess asked her husband not to witness the birth of their son, Ugayafukiaezu, but Hoori’s curiosity led him to spy on his wife.

Surprisingly, instead of seeing Toyotama-hime, Hoori saw a crocodile-like wani cradling his son. Apparently, shapeshifting into a wani was necessary for Toyotama-hime to give birth and she did not want her husband to see her in that state.

Toyotama-hime caught Hoori spying on her and felt betrayed. Not being able to forgive her husband, she decided to leave him and their son by returning to Ryugo-jo. She then sent her sister, Tamayori, to Hoori to help raise Ugayafukiaezu.

Tamayori and Ugayafukiaezu eventually end up getting married and giving birth to a son, Jimmu.

Mizuchi (蛟 or 虯) – The Four-Legged Dragon or The Hornless Dragon

Mizuchi was a water dragon that dwelled in the Kawashima River and would kill passing travelers by spewing out venom. Agatamori, an ancestor of the clan of Kasa no omi, went to the river and proposed a challenge to the dragon.

Agatamori cast three bottle gourds (calabashes) to the pool of the river which remained afloat on the surface of the water. He told Mizuchi to make the gourds sink or else he would have to slay him.

The dragon shapeshifted into a deer to try and sink the calabashes but was ultimately unsuccessful in completing the challenge. Thus, Agatamori slayed the dragon as well as the other water dragons at the bottom of the river.

According to the legend, the river turned red because of all the dragons Agatamori killed. The river was then referred to as The Pool of Agatamori, ever since.

Kiyohime ( 清姫) – The Purity Princess

Kiyohime, or simply Kiyo, was believed to be the daughter of a landlord or village headman known as Shoji. Their family was quite wealthy and was in charge of entertaining and providing traveling priests with lodging.

The tale of Kiyohime tells how a handsome priest called Anchin fell for the beautiful girl but eventually fought through his urges and decided to refrain from meeting with her again. This sudden change of heart was not taken well by Kiyohime, who went after the priest in rage.

The two crossed paths at the Hidaka river, where Anchin asked for help in crossing the river from a boatman. He also told the boatman to not allow Kiyohime to ride a boat so he could escape.

Upon realizing Anchin’s plan, Kiyohime jumped into the Hidaka river and started swimming towards his boat. As she swam, her great rage transformed her into a large dragon.

Anchin ran into a temple known as Dojo-ji and sought for help and protection. The priests at the temple hid him under a bell but Kiyohime was able to find him through his scent.

She coiled around the bell and banged on it loudly using her tail for several times. Then, she belched out a great amount of fire, which ultimately melted the bell and killed Anchin.

Japanese Dragons vs Chinese Dragons

As previously mentioned, a lot of people think that dragons are all the same. Furthermore, dragons are more often associated with Chinese mythology than Japanese mythology, which is understandable since a lot of Japan’s cultural practices and traditions are influenced by Chinese beliefs, one way or another.

However, there are actually a few differences between the dragons of Japan and China. In terms of their body/appearance, Japanese dragons are typically described to have three toes per foot, while Chinese dragons feature four or five on each. In addition, Japanese dragons are more serpent-like and carry a slender physique.

In terms of how they are portrayed in legends, Chinese dragons are usually given benevolent roles, while a lot of Japanese dragons are considered as malevolent beasts. Chinese mythology puts emphasis on the association of dragons with water bodies and regards them as bringers of rain for agriculture. Japanese mythology, on the other hand, often makes use of dragons to create scenarios that would put more focus on heroic deities.

It is worth noting, though, that the boundaries between what makes a dragon Japanese or Chinese are not particularly fixed. In some stories, Chinese dragons have been described to look like Japanese dragons. Furthermore, their roles of dragons in stories are not limited to the said stereotypes for each country’s mythology.

Japanese Dragons and Art – Tattoo Designs, Drawings, Paintings, and Symbols

When it comes to Japanese, or at least Japanese-inspired, art, the use of dragons is quite common. Over the many years and countless legends that have transpired, Japanese dragons have become an emblem for numerous concepts including strength, wisdom, prosperity, longevity, and luck.

How a dragon is depicted in a tattoo design, drawing, painting, or symbol greatly contributes to the overall meaning/concept. Some common variations include:

-

Ouroboros – symbolizes the cycle of life

-

A Sleeping Dragon – symbolizes a hidden power or strength that comes out when needed

-

A Gothic Dragon – symbolizes the primal instincts of man, i.e. fearlessness

-

A Tribal Dragon – symbolizes a deep connection with the culture of the tribe where the design originated from

-

A Rising Dragon – symbolizes progress and ascension

-

A Yin-Yang Dragon – symbolizes the proper balance of forces

-

A Dragon and Snake – symbolizes the conflicting ideas of superstition and science

-

A Dragon and Tiger – symbolizes the importance of having brains over brawns

-

A Dragon Claw – symbolizes fearlessness and power

-

A Dragon Skull – symbolizes that a difficulty has been conquered

-

A Dragon and Moon – symbolizes the connection of the sub-consciousness and nature

-

A Flaming Dragon – symbolizes passion, power, and sexual desires