The fact that countries around the world share specific parts of their way of life is nothing new. Everything from ancient legends, mythological creatures, music, food, and all kinds of art forms have similarities among its different varieties all over the world. One art form that has been practiced (and is still being practiced) since the Neolithic era (4500 BC to 2000 BC) is tattooing.

You can get a tattoo in almost any country you go to in the world. The perception that the public takes of having one and the meanings associated with them are what differentiate the tattoo culture from nation to nation. In Japan, the world of tattoos takes an interesting twist with its historically rich connections, ties to criminality, and underground movement for detaching the common bias against it.

The Etymology of The Japanese Word for "Tattoo"

The word “tattoo” has four different words in the Japanese language. There’s “tattoo”, or “タトゥー” which is the borrowed katakana version, then there’s shisei, (刺青), irezumi, (入れ墨), and horimono, (彫り物). It is most often referred to as “irezumi”.

Irezumi means, when directly translated, to “insert ink”. It is most oftenly written in Chinese characters. There are other characters that can be used, such as “紋身” pronounced as “bunshin”. “To decorate the body” is what bunshin is supposed to connote. Most Japanese combine two words to connote tattooing; one that connotes the method – “to pierce/prick”, and the other that connotes what is being pricked – the color green or blue.

Getting A Tattoo in Japan: The History Behind It

The Jomon period is when it all started. Known as the pre historical era of Japan, the Jomon period lasted from 14,000 BC to 300 BC. At this point in time, Japanese ancestors, together with the local Ainu (a set of indigenous tribes that lived in Japan) used tattooing as a part of their spiritual rituals. Proof of the possibility of tattoos being etched on people’s bodies was represented by figurines made from clay that belonged to this period. They had cord-like markings that looked like tattoos spread all around the figurine’s body and face.

During the first 300 years of Japan’s tattoo culture, it would be confirmed through written observations by Chinese travelers that the Japanese people who did have them used parts of, or their entire bodies as canvasses, as well as their faces. The varied designs of the tattoo would identify one’s status symbol, letting you differentiate between who had a stronger position in the community versus those who didn’t.

The Beginning of Japan’s Dislike for Tattoos

The Kofun period, which took up the next 300 years (it ended 600 A.D.) was when tattoos were not as acceptable as the norm as they used to be. This was because, during this period, tattoos were beginning to be utilized to stamp individuals who were convicts. Subsequently, the idea of a having a tattoo progressed toward becoming related to misconduct and criminality.

For about a thousand years (from the end of the Kofun period until the Edo period in 1603), Society was hot and cold about its perspectives towards tattoos. Regular folks still wanted to have their own tattoos done, despite criminals being known to brandish them.

The kinds of tattoos that offenders would get would sometimes be symbolic for their misdemeanor. Circles, lines, crosses, and Japanese symbols would be permanently painted on their faces and arms for easy identification, sometimes in the specific limbs of what they used, or where they caused harm to someone else. This wasn’t always the case, though. One example, the Japanese character for “dog” would be sprawled across the forehead of prisoners from a region.

The dawn of the Edo period is truly what changed Japan’s tattoo culture dramatically, for it ushered in a genre of tattooing styles called “Irezumi” that most people recognize as authentically Japanese today.

Woodblock Printing On Skin: A Shift in Mediums

When you see entire bodies tattooed with Japanese warriors, mythological creatures, and flowers, you’d notice that the art there is very much like the Japanese translation and illustration of a popular Chinese novel called “Water Margin”. Water Margin, whose original copy was done in vernacular Chinese, spread throughout Japan after one author named Kyokutei Bakin collaborated with illustrator Hokusai and made a book named “Shinpen Suikogaden”. In English, it was known as “the New Illustrated Edition of Suikoden”.

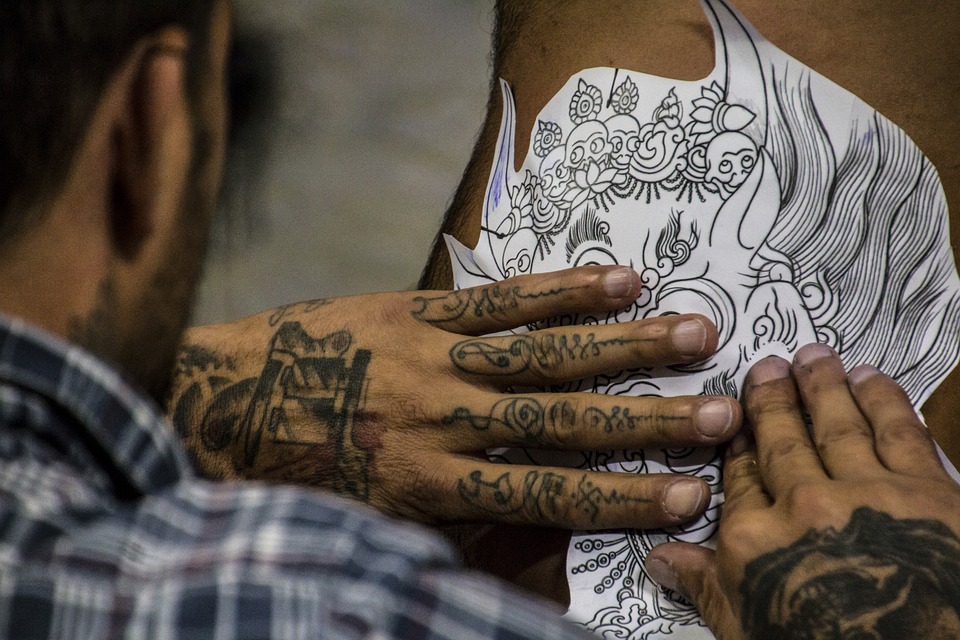

The fame of Shinpen Suikogaden exploded, with people wanting copies of its art on wood blocks. Slowly, instead of Chinese heroes being depicted on these wood blocks, woodblock artists (in Japanese, known as ukiyo-e) were being commissioned to create versions with Japanese heroes instead. Not long after, people were starting to ask for their bodies to be the mediums instead of wood blocks, resulting in being covered from neck to shin in woodblock ink.

The ukiyo-e did not change their tools for imprinting on blocks than they did for people. They used the same gouges, inks, and chisels. The inks that they used were exclusive to the Japanese – this was called “Nara black”, or “Nara ink”. This kind of ink was well-known for fading to a blue green hue over the course of time. The people who requested to be tattooed are argued by historians to either be either be of the castes in the lower class, rich merchants, or macho manual workers and firemen.

The Meiji Era, and the First Ban of Tattoos in Japan

Right as Japanese increasingly started getting into the trend of tattooing, alongside that period of history was the rampant colonization of the east by the west. The visit of Commodore Matthew Perry sparked a change in Japan that would inevitably lead to them trying to make a good impression on westerners.

Passing A Law Against Tattoos in Japan

Thus, in 1872, inking tattoos was banned. This sparked anger in the remaining Ainu tribes, as tattooing was part of their culture. Just as most things that do get outlawed, it continued illegally as an underground affair. Around 500 arrests were made from the beginning of the tattoo ban until its conclusion in 1948. From then on, thanks to the policy change by the U.S. occupation forces, the Japanese could tattoo and be tattooed without fear.

Why It’s Still Taboo To Have A Tattoo In Japan

Japan has had both a tarnished and at the same time, a beautiful relationship with tattoos. Aside from how it was used to mark felons in the past, it was also associated with the illicit activity for hundreds of years, from the 17th to the 20th century. Both major and petty crimes were related to this, most prominently criminal organizations forming their identity around having tattoos.

Some speculate that indoor bathrooms also have a lot to do with the lack of tolerance of the Japanese public towards tattoos. Before indoor plumbing was a thing, many people were bathing together and were desensitized to tattoos. Once private bathrooms were installed in every home, people became more sensitive to the display of a tattoo on one’s body and considered it deviant.

The Lack of A Tattoo Convention in the year 2017

The negative stigma that accompanies tattoos still has effects on modern-age Japan. The Japanese administration sometimes gives a hard time to individuals who have tattoos, so not that many people are willing to go out and publicly hold or attend a convention. For example, the Straight Life Tattoo Convention in Osaka was supposed to happen during April 16, but it was canceled suddenly, a week before it was supposed to take place. Suddenly, tattoo specialists around Osaka were apprehended for not having the correct permit to tattoo individuals.

Why You Can’t Bathe in An Onsen in Japan if You Have A Tattoo

Because of the lingering association with tattoos and trouble, many establishments also may not allow you to use their facilities if you have one. One of those establishments is an onsen; a public hot bath – apart from others, such as swimming pools and gyms. Following the tattoo’s ban during the Meiji period, which was only lifted by an administration that wasn’t theirs, the Japanese still have a hard time letting go of the stigma that comes with inked bodies.

This is slowly changing. With globalization, Japan’s youth have been increasingly adopting western culture and ideologies, embracing tattoos more than older generations have. From having around 200 to 300 tattoo artists in the 1990’s, there are supposedly thousands of them around Japan now.

The Most Famous Tattoo Artist in Japan

Horiyoshi III, who used to go by the name “Yoshihito Nakano”, is considered one of the top Japanese Tattoo Artists of the late 20th and early-21st century. The “Hori” in “Horiyoshi” means “engrave” in English. Nakano was granted the name “Horiyoshi III” because he was an apprentice to Yoshitsugu Muramatsu (also known as Horiyoshi I), and Muramatsu eventually granted him the title during 1971. Here’s a fun fact: Horiyoshi III’s tattoos were done by the son of his master Horiyoshi I; Horiyoshi II.

The work of Horiyoshi III revolves around traditional Japanese tattoos, irezumi. He specializes in working freehand and only started using electric tattooing machines after he met Don Ed Hardy. Unlike usual tattoo jobs, the content of the tattoo is decided upon by Horiyoshi III himself. Getting a full-bodied tattoo by Horiyashi takes thousands of dollars, as well as many trips back and forth over the span of 5 years.

Great Tattoo Parlor Choices Around Japan

Tattoo parlors are popping up around more now, you’ll find them in any city that is tourist-friendly. One of them is Honey Tattoo. This tattoo parlor, found in Ikebukuro needs you to call in if you want a tat session. Horimitsu, the main artist of the salon, is known for his traditional take on tattoos. His tattoo parlor has had a few celebrities come in to have tattoos done – one of them being John Mayer.

Another one is Red Bunny Tattoo, found in Tokyo. They’re available for the usual walk-in customer, which is great if you feel an impulse to get inked. Their inkers are well-experienced, each design is hip, and the inks they use are vibrant. One small tattoo costs 10,000 yen and can cost up to 12,000 yen an hour for big tattoos that take a lot of time.

Themes of Japanese Tattoos You Might Want for Your Next One

The Japanese are very fond of making tattoos based on their “yokai”, or mythological creatures, monsters, and beasts. Dragons are a favorite among many. A powerful person or character from Japanese folklore (such as the Suikoden novel) are also motifs used by irezumi artists. Shinto deities are known as “kami”, Buddhist deities, Buddha himself, geishas, samurais, and other Japanese religious and cultural aspects are also options.

Others enjoy having animals such as snakes, tigers, and koi vibrantly displayed across their bodies. Natural elements like wind, waves, and flowers are the next option. Flowers aren’t necessarily deemed as feminine, as they can be symbolized to mean many things. Flower examples are lotuses, chrysanthemums, peonies, and cherry blossoms. Along with flower themes come local Japanese plants, such as leaves from a Maple tree, or bamboo sticks. Use these ideas as a guide for your next tattoo.

A Museum of Tattoo Art and Tools in Japan

For tattoo enthusiasts who want to have a first-person experience with Japanese tattoo culture, there is a public tattoo museum that is handled by Mayumi Nakano, wife of Yoshihito Nakano, known as Horiyoshi III. It’s called “Bunshin Tattoo Museum”. Local and international tattoo memorabilia adorn the entire the museum, displaying arrays of traditional Japanese design, and collections of different inking tools used throughout past centuries. The museum’s address is 1-11-7 Hiranuma, Nishi-ku, Yokohama Kanagawa. The entrance fee is 10 yen.

Respecting Japan's Culture, as Well As Your Own Beliefs

It is advisable to cover up your tattoos when you visit Japan, for the sake of respect towards those who may be uncomfortable with their presence. However, just because it’s easier to blend with the crowd with your tattoos covered up doesn’t mean that your ideas and opinions about having them should change. Want that extra tattoo done in Japan? Go ahead and get it.

Consider making it part of your itinerary to have a special tattoo done in Japan. All you need to do is the necessary research. When should you do it? You can come during February or March, for the beginning of spring. It’s also fine if you book a trip to Tokyo in June or August, for summer. Getting a tattoo is a personal experience of a decision that will last a lifetime – where better else to have it done than the country that has had such a colorful history with it?